|

|

| themanager.org | Search |

Paving the road to profits

By Hanns Guenther Bollig

Managers running logistics operations have always struggled with bridging the gap between the sometimes controversial demands of their salesmen and the perceived requirements of cost efficient manufacturing. They are often stuck in the middle, trying to serve both ends. Yet they are most of the time unable to influence the most decisive factors which drive costs and service. This is why reaping the benefits of good logistics requires team effort and a holistic approach.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Taking a birds’ eye view:

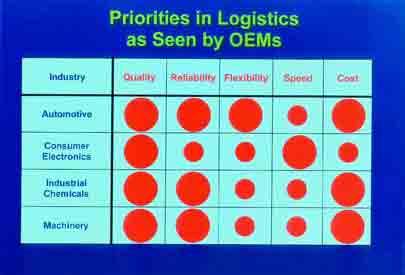

The automotive industry has always been the most demanding of all in terms of achieving the highest quality standards in their logistics processes. The efforts have been driven by the need to reduce costs and by the desire to respond quickly to customer demand and to safeguard their own production against any fault lines up and down the supply chain. Amongst all demands on Logistics, contrary to many expectations, speed is only of limited value. The reason is, that speed is only requested when speed has to compensate for faults which happened somewhere in the supply process. If all processes in the supply chain would be of highest quality and reliability, high speed in itself would not be required at all. The other important factor, flexibility, is defined as responsiveness in supplying varying quantities and continuously meeting fluctuating customer demands. But customer demand is not as unpredictable and erratic as commonly suggested. The ability to react flexibly to customer demand must be separated from the usual perception of speed.

The requirements which have to be met by the logistics functions vary significantly between industries and businesses. Supply side logistics, inter and intraplant logistics, distribution logistics, OEM logistics and after market logistics all follow different patterns and serve different market requirements. However, when I started consulting in automotive logistics, some 20 years ago, I was always given the same task: “Find the biggest possible savings in logistics whilst you must adhere to the market requirements for quality, reliability, flexibility, low costs and commonly accepted lead times”. I discovered quickly that it was always the same road which would lead to success, independent of industry, type of business or region. I found four principles being true:

1.More savings can be made through logistics than in logistics

2.More savings in logistics can be made by improving processes outside logistics than by improving processes inside logistics

3.Time is money. In logistics, gaining time is the biggest money maker of all

4.Good logistics keeps investment low and releases capital tied up in unproductive assets, making finances available for expansion and future business.

Working along the lines of these four principles would always do the trick.

1.More savings can be made through logistics than in logistics

The typical costs of logistics:

· inbound transportation,

· inter- and intraplant transportation,

· inter- and intraplant materials supply functions,

· all stages of warehousing and inventory carrying,

· outbound transportation,

· all stages of materials requirements and production planning,

· order processing and all other material flow related administrative and management functions

These account for between 15 percent and 35 percent of total costs of sales: the first figure being true for nearly all intra-continental supply chains, the latter figure being true for most intercontinental supply chains like overseas’ CKD and SKD operations. Most of the time, these costs of logistics are small, compared with the costs caused elsewhere by the effects of a poorly managed supply chain.. Viewed over more than 100 logistics projects, the typical side effects of poor supply chain management in the automotive industry are:

· 4 percent of cost of sales wasted by missing or wrong parts,

· 20 percent of installed production capacity wasted by inefficiencies in the planning and management process,

· 5 percent to 15 percent of excessive costs of parts and raw materials because of dual sourcing requirements or the exclusion of cheap but less flexible sources,

· 5 percent to 30 percent of lost sales due to unreliable and unsatisfactory market service.

· In total, these logistics related costs can amount to 30 percent and more of the whole value chain, wasting more than twice the total costs of logistics. Improving logistics must therefore never target logistics costs alone but must always seek to create the maximum value for the whole of the enterprise.

2.More savings in logistics can be made by improving processes outside logistics than by improving processes inside logistics

Whenever analysing the costs of logistics, one will inevitably find that many of the costs incurred in logistics are actually caused by factors which are beyond the reach of the normal logistics manager. Many logistics processes are caused by unexpected shortages in supplies, by poor quality of the production processes, by inefficient quality assurance processes, by poorly allocated resources or by unresolved conflicts of interests between different functions within a company. Most costs however are imposed on logistics by lack of an integrated approach between logistics and the other functions of the supply chain. Typically, such cost range between 20 percent and 60 percent of the logistics costs.

· Some examples of such penalty costs imposed on logistics from other functions are:

· costs of emergency shipments

· cost of temporary external warehousing

· large portions of inventory carrying costs

· large portions of line feeding costs

· under utilization of transport equipment

· under utilization of personnel

· overtime

The logistics manager may try to reduce waste within his processes or may try to negotiate the best deal with his forwarders and transportation agents. At best he will be able to save 10 percent to 15 percent of the costs of some of his processes. In order to achieve big savings, companies must seek to avoid the penalty costs imposed by others. Faultlines, causing such penalty costs, will become visible when measures are planned to fully eliminate wasted processes in logistics. Any remaining wasted processes keep people tempted to use them. Any remaining volume passing through a wasted process requires stand by costs and assets to keep the process functioning. As mentioned, cutting down wasted processes almost always needs changes which are outside the direct control of the logistics function. We must also recognise that high logistics costs are often an indicator of problems hidden elsewhere. Therefore, cutting down costs which are imposed on logistics from outside always bears the richest fruits. In my experience, for every $10 saved in logistics, $60 will be saved in adjacent areas if joint projects are pursued. Cost reduction programmes in logistics should therefore never be a task for the logistics management alone. It requires co-operation and teamwork across all functions of a company.

3.Time is money - In logistics, gaining time is the biggest money maker of all

In logistics, many people focus on speed. Speed is often valued highly and even more often mistaken as a sign of flexibility and high levels of customer service. In addition to speed, the “ideal” of one-off lot sizes is sometimes still seen as the ultimate means of achieving highest service levels at lowest costs. Yet, speed and one-off lotsizes tend to create excessive investments and huge capital tied up in bricks, mortar, machinery and personnel. However, in times when technology changes rapidly, when supplier relationships may be terminated from one day to the other, when price counts more than ever, we strive to achieve the advantages of mass production at the lowest possible investment costs. We must recognise that the desire for quick response and speed is often a result of failed attempts to manage processes properly. Speed has become a means to compensate failure. So has information management. The more speed I need, the more faults are in my processes. The higher my needs for continuous tracing, tracking and on-line status information, the more likely this is needed to compensate faults. The desire to know at any time and at any stage where a product happens to be, in what stage of a process it currently is and, if delayed, when it may be finished and made available to the customer, is mostly a result of failure to adhere to a planned schedule. It also reflects the need to communicate the results of this failure as quickly as possible to the customer. This, in turn, allows the customer to safeguard against the delay by changing his own plans, thus imposing the need for speed on his own operations. If there were no failures in the processes, if the quality of processes were perfect, the need for high speed and quick response would vanish to near zero. Thus information technology has taken a fair share in easing the pressure on quality and has diverted attention away from the ultimate goal of maximising reliability. It has also taken a fair share in hiding the fundamental structural problems often found in a process. By focusing on the individual event, managers are chasing to make good the damages caused by random failures. Yet they are unable to gather and evaluate the information in such a way, that the basic structural fault lines become visible and could be tackled.

Time is money. Like with most things on earth, there are natural patterns of behaviour and there are natural patterns of demand. The degree of randomness is limited. There may be X possible combinations available for the buyer of a car. Yet, not all these combinations are equally attractive to all customers. There are repetitive clusters and patterns of demand which remain near stable during the live cycle of a car, or follow foreseeable trends like the rapidly increasing use of air-conditioning systems or electronic controls. Today, the response time of supply chains lie well within natural variations of short-term demand and would allow more time for response than currently available. The man made fault lines in the supply chain override the normal demand patterns and repetitive clusters and make them nearly unrecognizable. Winning additional lead time and working towards repetitive patterns and natural clusters are some of the most important keys to cost savings. The more time is available for consolidation, the lower the cost. The more stable and reliable a process, the more time I have, the better can I plan and work towards a most effective programme. A good logistics manager seeks to win as much information lead time as he possibly can. He also seeks to get as much genuine information as he can get. He attempts to identify the natural patterns of demand and to eliminate the artificial noise and distortions created by the effects of inefficiencies and faults in the supply chain. This allows him to neglect constantly changing forecasts, overreaction and overproduction. They steal his time and his capacity. They are also the main cause for unexpected shortages because capacity has been wasted on other products which are now lying idle in stock and which may have already caused distress and havoc in production. He will not work towards maximising flexibility and managing chaos but he will work towards improving quality in the processes. He will focus on creating the maximum of stability and reliability. In addition, he will seek to work towards typical and accepted lead times at all stages of the value adding processes: In the automotive world, such typical cycles are: 1,2, 4, 8, 24, 48 hours, 5 working days, 10 working days, 20 working days. He will then try to keep all processes within these agreed lead times as stable and reliable as possible. It is not important to be faster than the accepted lead times, but not meeting them costs everybody dear. The degree to which unreliable production processes and failure to cope with them can make logistics a nightmare can be illustrated by the example of the steel industry. High quality cold rolled steels are some of the automotive products which are worst effected by unreliable production results and other fault lines in the production process. If production of flat automotive steels would enjoy a 100 percent reliable production process, nearly all grades of flat steels could be made to order within three weeks. Logistics would be easy, inventories low, single sourcing in steels an easy task. Yet, in reality, production can take any unpredictable time between 3 and 18 weeks. Good logistics will identify these variations by type of steel, product or process. Priority actions for process improvements will then be set, safeguards be taken. Again, the problem is, that logistics can not achieve this alone. Every link in the supply chain and every manager in the process has to work towards this common goal.

The goal of quality and reliability is already very difficult to achieve within one single company. However, today’s modularised supplies and the formation of new supply consortia make it more complex and more necessary than ever. Not only the various departments and functions within one firm have to participate in a collective effort but the whole group of different companies has to team up. Modern logistics managers must therefore co-operate beyond the boundaries of their companies. OEMs and the large first tier suppliers should take the lead.

4.Good logistics keeps investment low and releases capital tied up in unproductive assets, making finances available for expansion and future business.

In my early days, we were called in by a large producer of consumer products. Only three years ago, they had invested several Millions in two fully automated warehouses which should serve as distribution centres for their business. During the period of use, the storage capability of the warehouses started from being fully utilised to being half empty whilst the throughput capacity became too low and customer expectations could not be met. The designers and engineers of these centres, listening to the complaints, refused to take responsibility for this development. They claimed that they had designed the warehouses in full compliance with the specifications given to them at that time. However, both, the company and the designers, had failed to recognise that product scope, customer demand patterns and packaging sizes can change within comparatively short periods of time. They had wasted these millions in investment by not providing for change and by not building in the flexibility such a business needs.

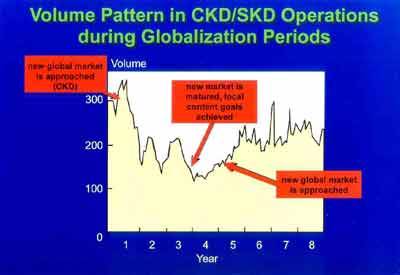

A similar problem, yet on a much larger scale, is facing the automotive industry. In a phase of global expansion, logistics must provide the means to open new markets at lowest capital risks and greatest possible flexibility. In setting up global supply chains, OEMs and suppliers alike face demand for high levels of local investment. Equally high are the demands for extended facilities at home in order to support additional global shipments and international supply links for production parts. However, this demand will not be stable. Globalisation is requiring continuous ups and downs of capacities (see the graph showing the typical volume development of CKD/SKD operations). Despite the temptation to provide for the biggest throughput, logistics must remain lean all the time. Furthermore, remote operations require progressive decentralization of services hitherto provided centrally by own staff: quality assurance, packing, external consolidation points and service centres are some examples for decentralization needs. Keeping in mind the variability of the business and the need to keep investment low, outsourcing is a valid answer. Giving away services previously provided by own staff appears a hard thing to do. The main concerns often used as an excuse to keep tasks in house are perceived problems with reliability, capability and lack of experience of external providers. Yet, logistics must be a leader in flexible performance, desinvestment and decentralisation. Too much capacity is still installed in bricks and mortar and own personnel.

I often find a strong communication gap between the parties involved. Weak logistics organizations, lacking ability to lead and to convince, missing information beyond the boundaries of their own functions, segregation and separatist approaches from all side makes the integrated processes of logistics difficult to improve. I am of the opinion that substantial improvements can only be achieved by looking beyond the boundaries and by implementing fundamental changes in processes, behavioral patterns and customer focus. The team player, integrator and networker is now in demand, not the organization fetishist.

If you want to know more, please contact us: Automotive Advisors & Associates